Buddha in the Float Tank

On the absurdities of outward journeys and the clarity of inward journeys.

What is the float tank? What does it teach us about perception, selfhood, and “enlightenment”?

In a nutshell, the tank is a vehicle for inward exploration. By floating motionless in a chamber insulated from lights and sounds, one goes deep into oneself and, perhaps paradoxically, discovers that the self isn’t there in any conventional sense. The Buddhist teachings of non-self and emptiness are offered by the dharma of darkness.

But you ask, “Isn’t floating in a dark, silent tank and doing nothing a waste of time?” Wouldn’t you rather go somewhere? Do something?

In travel and pilgrimage, many of us seek insight and illumination. Few of us think to also take the innerward journey of discovery. In my experience, there’s much to learn in both directions. But the lessons of travel, however fun, can often be comically absurd, sometimes missing the target completely.

Here, I reflect on two of my past travels and compare these to the lessons of the float tank.

The Great Pyramid of California

My wife and I once stopped in the desert to see a great pyramid. No, this wasn’t Egypt. Rather, we had stopped in Felicity, California, a town with a single digit population one finds just minutes before crossing into Arizona on Interstate 10. Only two and a half miles to the south is the international border with Mexico. What brought us to this bizarre microcosm in the Sonoran Desert?

It sounded like, and plausibly looked like, something born of a religious zealot’s midlife crisis: the Museum of History in Granite. The deserts of the American Southwest abound with a strange brand of revivalism, often a sort of hybrid between New Age and Christian evangalism. One need look no further than the permanent folk art installation Salvation Mountain, just 50 miles from Felicity in Slab City, California, which looks like the manic LSD creation of a Baptist preacher. The branding of Felicity, the self-proclaimed “Official Center of the World”, gave a subtle vibe in a similar, albeit more ambiguous, direction of spiritual gradeur and woo. As my wife and I bought our 10 dollar entry tickets, I wondered if this strange museum wasn’t simply a front for an eccentric cult.

It wasn’t. Or at least, that’s the conclusion I reached after reading many granite slabs recounting the history of humanity. These slabs, constructed around a stone pyramid, form the Center of the World, or so the story goes. I still felt like someone wearing a propeller hat was winking at me. Limited by our short time—a brief pit stop en route to the Kofa National Wildlife Refuge in Arizona—I couldn’t do a deep read of the entire museum. I cannot say with confidence that the museum doesn’t contain anything that wouldn’t be labeled as vandalism if written into Wikipedia. Nor can I say that it does. The Center of the World does not pretend to be secular: a nondenominational chapel on a hill overlooking the museum nods to some religious inspiration. But to the best of my knowledge, the Museum of History in Granite is an earnest, albeit eccentric, effort to recount human history on—what else—slabs of granite.

A few granite slabs did recount the history of the world’s major religions. Erected here was a typically western take on Buddhism. “Through meditation, [the Buddha] concluded that spiritual peace lay in the complete forgetfulness of self,” the granite tells us, with an etching of the Great Buddha of Kamakura decorating the panel.

My objection is with the word “forgetfulness”. Perhaps it is a sincere mistranslation of a sutra, or just an ignorant mistake, but the resulting impression is that one must obscure consciousness to ignore the self, as though drinking oneself into a haze. Rather, the Buddha taught the opposite—that in a clear state of awareness, the self is an illusion.

But as I learned at my next destination, visiting the Great Buddha of Kamakura doesn’t clarify much.

The Great Buddha of Kamakura

Nearly four years later, my wife and I visited the Great Buddha of Kamakura in Japan— the same statue depicted on the granite slab in Felicity. Almost eight centuries old, it’s a sublime bronze statue sitting on the grounds of a temple named Kōtoku-in. Indeed, only the Buddha himself could appear so composed amongst a mob of tourists competing for selfies.

Visiting this famous statue was one of the highlights on my trip to Japan. But, as with Felcity, I doubt that any pilgrim who visited Kōtoku-in this past summer learned much about Buddhism. At least not from this hive of tourists. As we left the temple, I saw someone wearing (or was he also selling?) a t-shirt with the Buddha’s face as the Starbucks logo. Lucky for them, the Buddha is too detatched to react to such commercialization of his temple (that, and he’s made of bronze). In Kamakura, there will be no Jesus cleansing money changers from the temple.

Perhaps pilgrimage can teach one a thing or two about enlightenment. Especially if you speak the native language. For all I know, Japanese language dharma was everywhere, flying under my radar. All I can say confidently is what’s worked for me. And for me, there is no greater pilgrimage than the pilgrimage into darkness.

Dharma in darkness

Which brings us back to the float tank. I’ve floated at least 20 times in several different tanks, enough experience go give you a tour. Come back from Japan with me, and let’s begin the journey inward.

The tank1 is a lightproof, soundproof chamber filled with saline water. This solution, saturated with Epson salt, is so dense that one floats effortlessly, with no muscle tension. What’s more, the water is heated to the temperature of the skin. Thus, besides being dark and silent, the tank is also absent of any gravitational, tactile, or thermal sensations. The so-called proprioceptive sense, which operates outside the traditional five senses to locate limbs and other body parts in space, also goes dormant in the tank. Once the body is still, floating effortlessly, all that’s left is the mind.

Except, the mind is all you ever had to begin with. Everything you ever see, hear, or touch is happening in the mind. How could it be otherwise? Nothing really changes in the tank. The tank just reveals the nondual nature of consciousness.

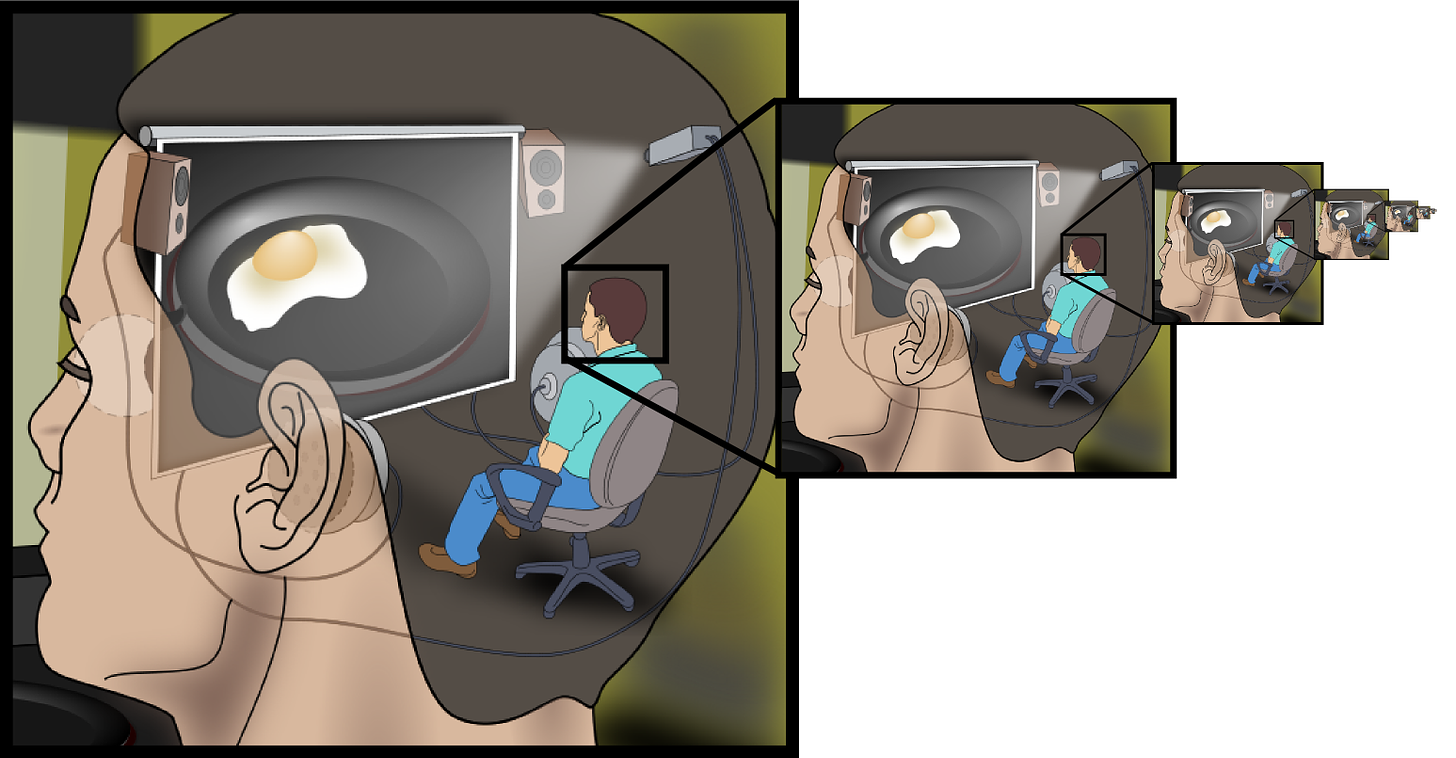

Here, we need to get philosophical for a moment. The term nondual emphasizes that subject and object are not separate. The world is not “out there” while the self is “in here”. The perceiver and the perceived are one. Consider this illustration below from Wikipedia. If “I” am located somewhere internal to my head, watching the world outside like a person in a movie theater, then how does this little homunculus perceive the inside of the theater? There would need to be a little person in his head, and so forth, ad infinitum.

It’s one thing to grasp nonduality intellectually. It’s another thing entirely to grasp it through direct experience. The illusion of separateness from the world is so convincing that we rarely glimpse through it.

The float tank makes it easier to see through this illusion. The ordinary sense of being a subject in the head looking out at objects in the world ceases when that world disappears in the tank. One no longer feels that they are experiencing things from a distance. Rather, there is just consciousness.

There’s another curious consequence of the zero-stimulus environment called dissociation, or extreme psychological detachment. Here, we encounter a paradox: the body is perceived more clearly, but in a new, non-self context. On the one hand, it’s unsurprising that one becomes more aware of bodily sensations in the float tank, for these are the only sensory channels that are still buzzing with information. Indeed, enhanced cardiorespiratory awareness in the tank has been reported in scientific research. On the other hand, because one no longer feels like a subject internal to the body, the body is no longer the center of awareness. Nondual awareness is centerless, which probably explains reports of out-of-body experiences in the tank (including my own brief experience).

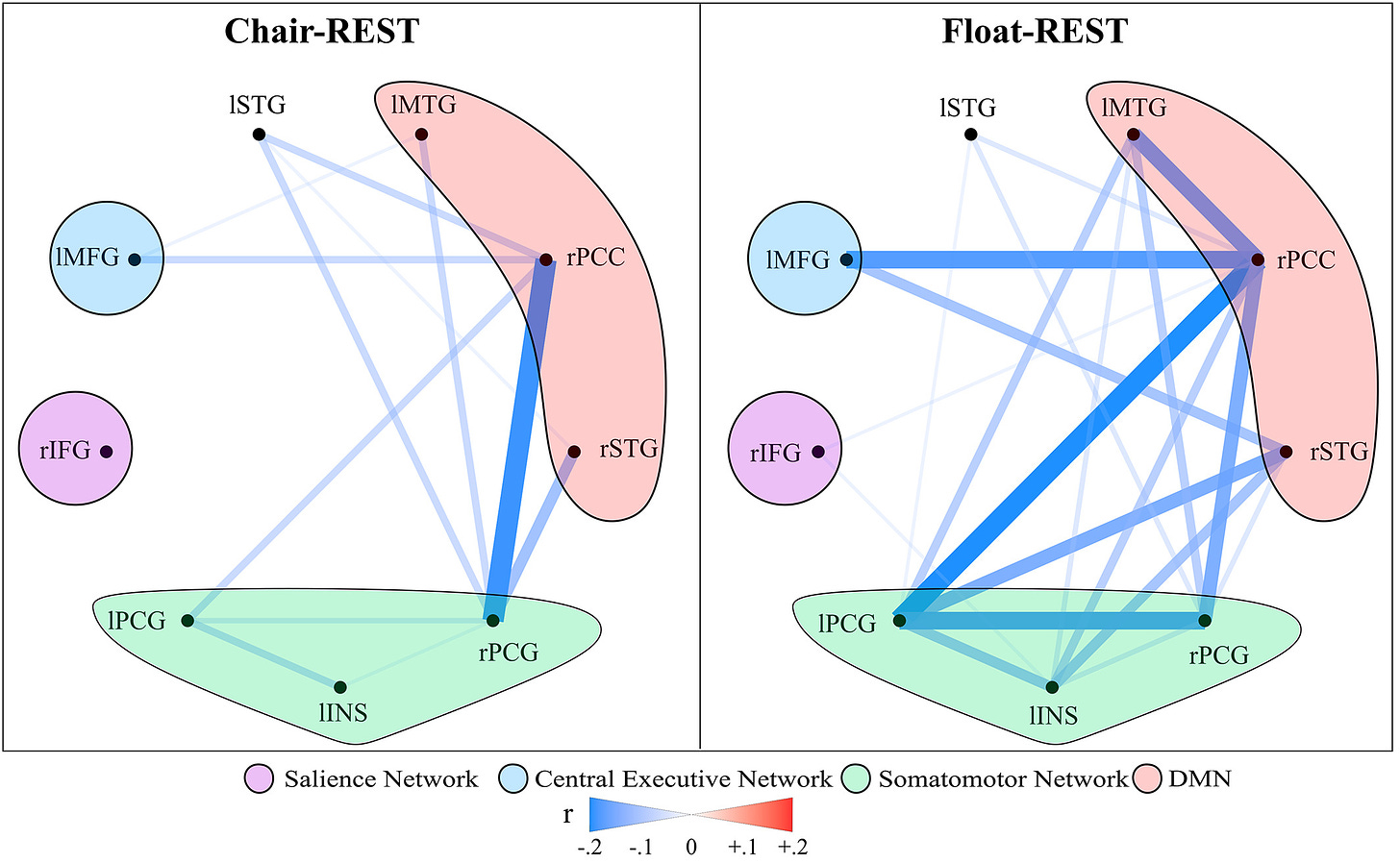

Except where noted otherwise, the above reflections on floating and nondual awareness are anecdotal, based on my own float sessions. However, the idea that floating alters self-perception in a manner similar to meditation or even psychedelics drugs is also supported by a neuroimaging study of healthy volunteers who had brain scans before and after three float sessions. These volunteers showed changes in the brain’s default mode network—widely regarded as a neural substrate of the autobiographical self—similar to what has been reported in other studies of meditation and psychedelic substances like psilocybin and LSD.

Of course, there’s still much that we don’t know about how floating compares to other altered states of consciousness, and whether it has similar (and likely safer) therapeutic potential as psychedelics seem to have for mental illness. I strongly advocate for future research to address these questions.

The journey of a thousand miles starts with zero expectations

Let’s suppose you’re convinced that the inward journey is worth it. Maybe you’ve found a float center near you and you’re curious to give floating a try2. However, you might not be sure how to start. “What should I actually do when I get in the tank?” you wonder.

In short, focus on your breathing and, most importantly, forget everything you’ve read here. The most valuable experiences one can have in the float tank are those that happen spontaneously. Grasping at an experience, begging something magical to happen, almost guarantees that it won’t. You can revisit the main concepts in this post after you’ve already glimpsed them.

Unlike meditation on the cushion, which can often be guided using a teacher or an app, meditation in the tank is usually silent and unguided. However, some float centers have speakers installed in the tank for customers who want to listen to music of meditations instructions. If you find such a float center, I’ve posted a guided meditation with float instructions on Youtube.

Feel free to contact me for the audio file3. I can’t guarantee that it will sound crisp or even intelligible underwater, but you can also use the timestamps in the video to skip between each silent segment and listen to the instructions ahead of time at home, preparing you for your float.

Closing thoughts

The Buddhist Monk Dogen, founder of the Soto school of Zen Buddhism, once wrote, “Take the backward step and turn the light inward.”

To many of us, especially in the West, a backward step sounds like regress, just as sitting or floating doing nothing sounds like a waste of time. If this is your intuition, I invite you to reconsider.

Whether on a cushion or in a float tank, begin the inward journey with Dogen’s backward step.

If this were a paper book, I’d leave a blank page here. Maybe this would be for the reader to contemplate peace, stillness, and openness, or maybe it would just be a fun joke. Alas, on Substack, I don’t think 50 blank lines will have the same effect.

But if you’ve read this far, you know that the inward journey isn’t about reading or thinking. It’s about experiencing.

Socretes is often quoted as having said, “The unexamined life is not worth living”. Whether that’s true or not, the unexpereinced life is clearly not worth living. For it is qualia, i.e., subjective experience, that gives life value.

There’s rich qualia to be found in both inward and outward journeys. Whichever journey you take, discovery what it’s like to be you. If you pay close enough attention, everything else will follow.

It is sometimes referred to as a “sensory deprivation tank”, but this term is disliked by researchers such as Justin Feinstein because of its negative connotations that impede research and, moreover, the fact that floating actually enhances internal sensations from the body.

Usual disclaimers apply: if you feel unsure, talk to your physician first before floating, especially if you have a severe mental or physical health condition.

You can direct message me here on Substack, or use the contact form on my website, joelfrohlich.com