Is general relativity pseudoscience? Serious thinkers a century ago often thought so.

Are counterintuitive predictions, media sensationalism, and the untestability of a subset of claims enough to warrant the label "pseudoscience"?

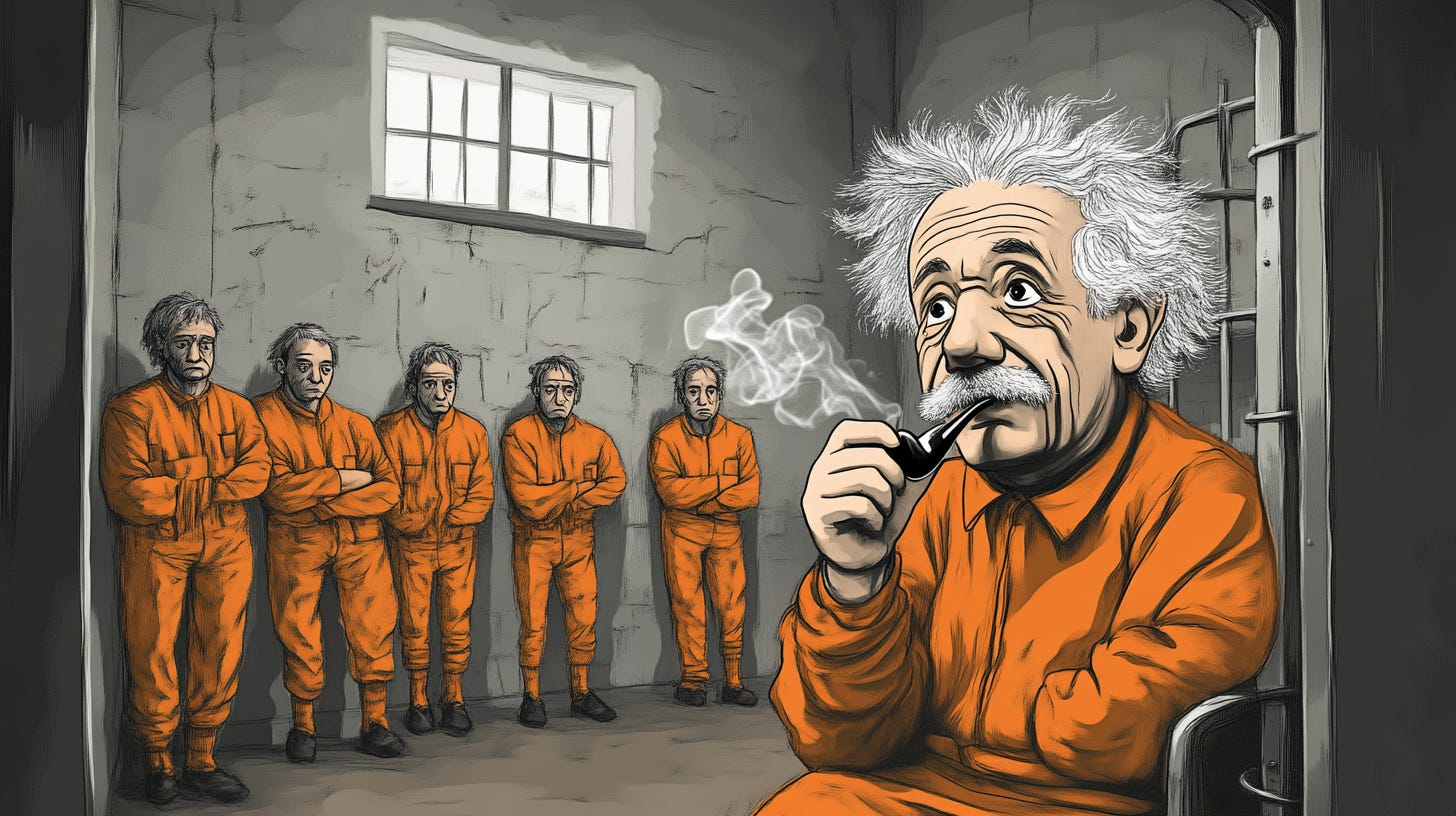

Yesterday, I uploaded an opinion paper that I coauthored with two colleagues from the Institute for Advanced Consciousness Studies, Adam Safron and Nicco Reggente, to the preprint server PsyArXiv. We argue that a pseudoscience accusation launched late last year against a prominent theory of consciousness, integrated information theory (IIT), hinges on reasons that could just as easily be applied to a much more established and empirically verified theory like Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity, one of the most successful scientific theories of all time. (What is IIT? Read our opinion paper for a broader background).

Yesterday’s upload is already making a stir on Blue Sky Social. What some commenters there have missed is that we are not equating general relativity with IIT (our paper was explicit about that). We are saying that, if you try hard enough, you can use the arguments launched against IIT-concerned to “take down” even the most established scientific theories.

Published over a hundred years ago in 1915, general relativity remains, to this day, the accepted theory of gravity for nearly all physicists. But could it be pseudoscience?

Imagine opening a newspaper, or clicking a reputable link online, and reading the following editorial:

The General Theory of Relativity as Pseudoscience

We, as researchers with relevant expertise, wish to express our concerns regarding recent media coverage celebrating the general theory of relativity, or "general relativity," as a leading or dominant theory of gravitation. Proponents of general relativity have repeatedly conveyed these claims of dominance to the public over the years. While general relativity is an ambitious theory, some scientists have labeled it as pseudoscience.

General relativity makes unscientific and magicalist claims about the nature of time and space. According to general relativity, time does not objectively flow and the future is just as real as the present of past, a strange philosophy known as eternalism. Tunnels or "wormholes" through spacetime might allow for time travel. The theory cannot explain the rotation of galaxies without invoking spooky "dark matter" which is never seen yet outnumbers ordinary matter several times over. It also resists compatibility with the highly successful field of quantum mechanics, e.g., a graviton particle has never been discovered.

Most absurdly, general relativity even predicts that gravitationally collapsed stars form singularities in spacetime, a solution to Einstein's field equations that amounts to division by zero and which is untestable because no information can escape from the event horizon of this so-called "black hole". Furthermore, the theory gives contradictory answers to the question of when a person falling into a black hole would cross the event horizon. A distant observer might watch this person fully disappear behind the event horizon even while, in the doomed astronaut's frame of reference, the crossing of the event horizon takes an infinite amount of time to occur. Surely, these deeply counterintutive predictions represent a departure from science as we know it.

Considering its eternalist commitments, we believe that until general relativity as a whole is empirically testable, the label of pseudoscience is warranted. Unfortunately, recent events and heightened public interest make it especially imperative to address this matter. Much critical nuisance was lost in media coverage that featured headlines such as "Revolution in Science, New Theory of the Universe, Newtonian Ideas Overthrown," as reported by The Times of London, and "Lights all askew in the heavens. Men of science more or less agog over results of eclipse observations. Einstein theory triumphs" as proclaimed by The New York Times. These 1919 headlines do not make contact with some core predictions of general relativity, which must wait nearly a century for confirmation until technology exists which can detect gravitational waves.

If general relativity is either proven or perceived by the public as such, it will have a direct impact ethical issues including fatalism, free will, and predestination, as the theory characterizes the future as being already predetermined in such a way as to suggest that choice does not exist and criminals could not have done otherwise. Our consensus is not that general relativity decidedly lacks intellectual merit. But with so much at stake, it is essential to provide a fair and truthful perspective on the status of the theory. As researchers, we have a duty to protect the public from scientific misinformation. Therefore, we hope to make clear that despite its significant media attention, general relativity requires meaningful empirical tests before being heralded as a ‘leading’ or ‘well-established’ theory. Its idiosyncratic claims and potentially far-reaching ethical implications necessitate a measured representation.

So, are you convinced?

You've just read a satire1 of the IIT-takedown letter I mentioned at the beginning of this post. Read the original letter for yourself, and you’ll see how closely the satire mirrors its arguments and structure.

Above, and in my response letter coauthored with two colleagues, I've shown how similar arguments — deeply counterintuitive predictions, untestability of certain claims, media sensationalism — could also be used to label general relativity, one of the most successful scientific theories of all time, as pseudoscience. Indeed, a theory can be overall scientific despite counterintuitive predictions, media sensationalism, and untestability of a subset of certain claims, so long as the relevant core predictions of the theory are testable.

In its early days and even today, the general theory of relativity had, and continues to have, many critics. As with IIT, many of these opponents once joined forces to publish a piece of criticism against general relativity. The resulting book, Hundert Autoren gegen Einstein2 or "A Hundred Authors against Einstein" in English, was penned by 28 critics and identified a further 93 critics to reach a count of 121 individuals skeptical of relativity theory, for which the book is titled (note, this is nearly the same number of signees on the letter attacking IIT). As with the recent pseudoscience accusation against IIT, prominent criticism of relativity in "A Hundred Authors against Einstein" was superficial and based on plausibility arguments.

Still other books were written criticizing general relativity. One of Einstein's most zealous critics, Charles Lane Poor, wrote the following in his 1922 book Gravitation versus Relativity3:

The Relativity Theory, as announced by Einstein, shatters our fundamental ideas in regard to space and time, destroys the basis upon which has been built the entire edifice of modern science, and substitutes a nebulous conception of varying standards and shifting unrealities. And this radical, this destroying theory has been accepted as lightly and as easily as one accepts a correction to the estimated height of a mountain in Asia, or to the source of a river in equatorial Africa.

Does the substance of this argument (or lack thereof) sound familiar? And while Poor is hardly a household name, Einstein's contemporaneous critics also included more prominent individuals who are remembered to this day, including Nikola Tesla, who dismissed Einstein’s idea4 as “a mass of error and deceptive ideas” and, even more scathingly, “a beggar, wrapped in purple, whom ignorant people took for a king.”

Imagine that the satire from this post had been written by some of these critics. Of course, reading the satire this way results in some anachronisms — the term "black hole" was not coined until 1967, over a decade after Einstein's death, and quantum mechanics might not have been accepted by the time when such a letter would have been written. But, that is beside the point, as all criticisms from the satirical letter have been aimed at general relativity at some point in history.

Would you take this satirical letter's accusation of pseudoscience seriously? And if not, what does this imply for the recent characterization of IIT as pseudoscience?

The CC-By Attribution 4.0 International license of the letter gives me permission to adapt the original text, with attribution to Fleming et al. 20235, in this post.

One person objected to me that this isn’t very satirical because he didn’t find it funny … most definitions of satire don’t require humor though.

Israel, Hans, Erich Ruckhaber, and Rudolf Weinmann, editors. Hundert Autoren Gegen Einstein. R. Voigtländer, 1931. See archived text here.

Poor, Charles Lane. Gravitation Versus Relativity: A Non-technical Explanation of the Fundamental Principles of Gravitational Astronomy and a Critical Examination of the Astronomical Evidence Cited as Proof of the Generalized Theory of Relativity. GP Putnam, 1922. See archived text here.

Fleming, Stephen, et al. "The integrated information theory of consciousness as pseudoscience." PsyArXiv, 2023.